Furniture: the non-art object.

The manner of seeking something profound, real, and truthful in art is too often pigeonholed and associated with the Western aesthetic convention of connoisseurship, which is unfortunately limited to the eyes and knowledge of scholars and the academic milieu (my cynicism, sue me). Contrastingly though, the ethical values of art are more often linked to the specific political, cultural, and economical systems found in everyday life, so arguably something as perfunctory as furniture could be esteemed as an art object, no?

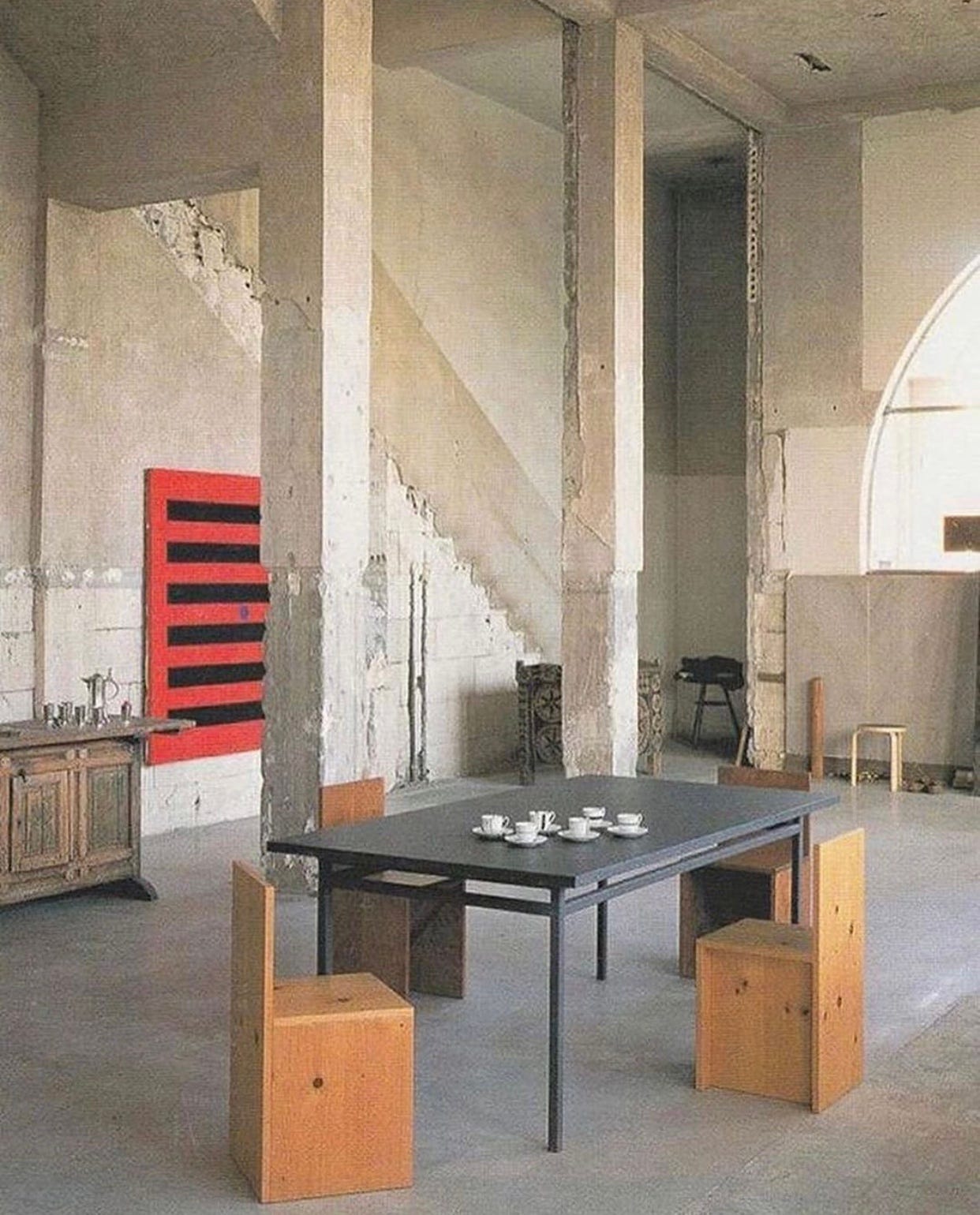

Probably not, no, according to formalist art critics who have largely dismissed the intertwining of art and everyday objects, with a few Duchampian exceptions. Historically though, many artists have explored with furniture/construction-based practices: Isamu Noguchi, John Chamberlain, Forrest Meyers, to name some, but heralding a significant example: Donald Judd. Born in 1928 in regional Missouri, Judd’s practices in art and design revolved around a holistic approach, grounded in rigorous spatial principles. The posterchild for American Minimalism, his furniture adhered to key formal properties: planes, rectangles, and right angles. Yet as an applicable item would not adhere to a specific identity: a chair could be shelf, could be a coffee table, could be a bedside table, etc.

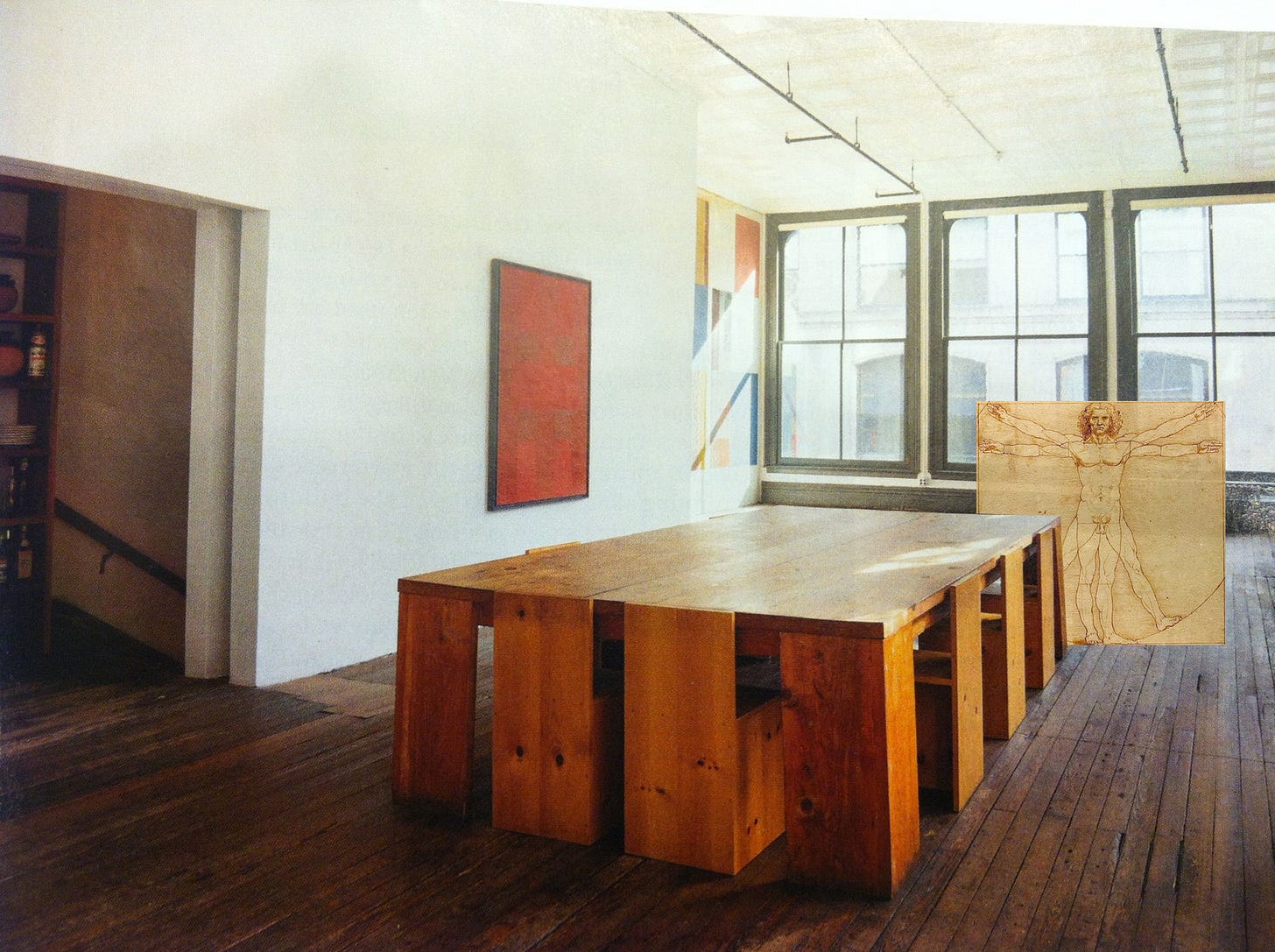

Donald Judd always maintained that the distinguishing factors in the comparison of his furniture practice to his art/’specific objects’ practice were determined by the need for functionality and appropriate human scale. Think: Leonardo Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man and his need for his feet to touch the ground when he is sitting on a seat. I do feel though there is more gossamer to his furniture than just the proverbial form following function, that Judd generated and modelled his furniture as paradoxical counterparts, that blended into the totality of his own living environments and installations. The man nailed his bed to the floor of his New York City home.

For my birthday this year I received one of the most seminal and sentimental gifts from a friend of mine: a bootleg Donald Judd Corner Chair 15, made by her (Olivia) and our friend Jarrod. Authentically designed and constructed in anodized aluminium by Judd Furniture and retailing $8,000 USD, Liv and Jarrod reinterpreted the form into MDF, and adopted similar construction methods as other Donald Judd plywood and timber furniture. Notably, the absence of mitring, and instead, parts being fixed by butt-joints, a signature of Donald Judd’s designs, yet ironically, considered rudimentary in Western carpentry schools of practice…

Add to cart.

Of the negotiation between sculpture and furniture, Judd once wrote: “The difference between art and architecture is fundamental. Furniture and architecture can only be approached as such. Art cannot be imposed upon them. If their nature is seriously considered the art will occur, even art close to art itself.”

In 1992, in the lead up to Documenta IX in Kassel, Austrian artist Franz West went to every single Dry Cleaner in Vienna, asking for old, abandoned Persian rugs. Those rugs were repurposed to undulate and lay simply over his metal and foam frames: he was creating 72 sofas for his artwork Auditorium. Have you seen photos of Sigmund Freud’s consulting room? They looked like that. Auditorium was a site-specific installation and piece of sculpture/furniture where people could meet, talk, relax and think. Earlier, in 1989, at his solo exhibition at MoMA PS1, West had made spindly metal seating that he felt was too uncomfortable, so to soften the seats he would place the days’ newspaper on each one.

Like the aforementioned Vitruvian Man, Franz West’s practice centred around human scale, touch and tactility. He created painted plaster-based sculptures that asked his audience to handle, touch and physically immerse themselves within. So it doesn’t come as a surprise that he thought of furniture in sculptural terms, and approached their design and creation in accordance with his sculptural practice. West questioned the practicality of art and our cerebral and physical response to it and how it should be experienced, and accordingly suggested to us the possibility that furniture could be a sculpture, and also a usable social experience. He termed his furniture as ‘adaptives for the human body at rest.’

18 months ago David Zwirner Gallery sold a large collection of his furniture, posthumously. Sofas, epoxy-resin and metal dining chairs, chaises; all sold between $12,000 and $80,000 USD, which may seem like large amounts of money, but comparatively his plaster-based sculptures still sell at auction for sums 10 times those amounts. $12,000 for a Franz West artwork is a bargain.

‘I came to art via the places where artists meet, places where you would go and sit’ - Franz West.

‘Ahh I’m a designer… Carrie Bradshaw… Carrie Bradshaw designs’ – Carrie Bradshaw lying about her profession to acquire the elusive interior designer discount.

There certainly is a cultural hierarchy between art and furniture and their identities, with the conventional argument for defining them being according to whether it has visual appeal or functional utility. Furniture in situ shouldn’t always be about the aesthetic and its function though, rather its immediacy of the physical and mental interaction between itself and the user in a particular space. Its own installation.

-Antonia